Analysis: Investors eye uncharted waters as quantitative tightening looms in Canada

TORONTO, Feb 9 (Reuters) – As the Bank of Canada prepares to shrink its bloated balance sheet, investors say the move could enable expected interest rate hikes to have more far-reaching impact on economic activity.

Canada’s central bank, unlike the U.S. Federal Reserve, has never previously attempted to shrink its balance sheet, a process known as quantitative tightening (QT), having bought government bonds in large scale for the first time during the pandemic.

It currently owns about C$420 billion ($330 billion) worth, or 42% of the market, eclipsing the 28% slice of the U.S. market held by the Fed.

Reducing its share of the bond market could transmit monetary policy more effectively to the economy. That’s because borrowing costs for households and businesses tend to be determined by longer-term rates rather than the very short-term rate that is set by the BoC.

“Because they own so much of the bond market, the bigger risk is that they don’t roll off quickly enough,” said Andrew Kelvin, chief Canada strategist at TD Securities.

Another potential advantage of QT would be to reduce the reserves that the BoC created to pay for bond purchases.

Unlike the U.S. system, banks in Canada are not required to hold reserves at the central bank, while the excess liquidity has driven CORRA, a measure of the cost of collateralized overnight lending between banks, below the BoC’s 0.25% target.

CORRA is expected to become the primary interest-rate benchmark in Canada, likely referencing trillions of dollars of derivatives.

The BoC is currently in the reinvestment phase of its asset-purchase program, buying about C$1 billion of bonds per week to replace those that mature. Analysts say the bank could announce a shift to QT as soon as the March 2 policy announcement, should it hike interest rates then as expected, or at the following meeting in April.

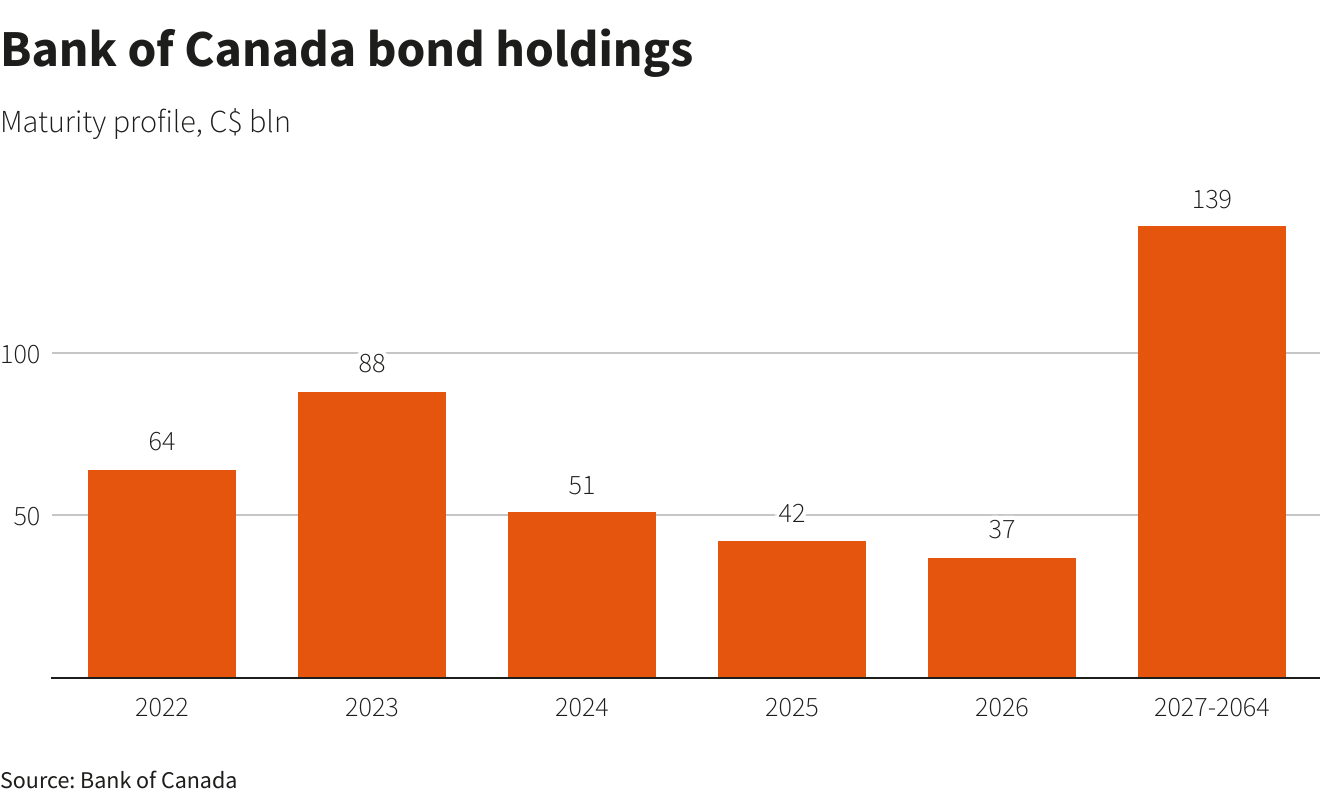

The BoC has said it will keep its bond holdings constant at least until it begins raising rates. Rather than selling bonds, it is expected to rely on debt rolling off its balance sheet as it matures.

A so-called passive approach is likely because of the maturity profile of the BoC’s balance sheet, say analysts. Nearly 50% of its holdings mature by the end of 2024.

With uncertainty around a number of QT issues, including the need to cap the pace of roll-off and the optimal balance sheet size in future years, analysts are standing by for guidance from the bank.

Prior to the announcement, “they’ll talk us through how the sausage is made,” said Ian Pollick, global head FICC strategy at CIBC Capital Markets.

For the market, moving to QT would increase the amount of debt that it needs to absorb. By itself, that could be taken in stride, say analysts.

The risk comes from central banks globally also moving to shrink their balance sheets. The Bank of England last week announced the start of QT and the Fed could do so later this year. read more

The last time the Fed tried QT, from the end of 2017 to autumn 2019, it only managed to shrink the balance sheet by about 15% or so before it ran into trouble. read more

“The more central banks that are concurrently unwinding their balance sheets, the more potential disruption there may be for markets which have become addicted to such purchase program,” said James Athey, investment director at Aberdeen Standard Investments, in London.

($1 = 1.2713 Canadian dollars)

Reporting by Fergal Smith Editing by Denny Thomas and Sam Holmes