Explainer: What is China’s ‘common prosperity’ drive and why does it matter?

BEIJING, Sept 2 (Reuters) – President Xi Jinping has called for China to achieve “common prosperity”, seeking to narrow a yawning wealth gap that threatens the country’s economic ascent and the legitimacy of Communist Party rule.

“Common prosperity” as an idea is not new in China, but a sharp escalation in official rhetoric and a crackdown on excesses in industries including technology and private tuition has rattled investors in the world’s second-largest economy.

Xi, poised to begin a third term in 2022, is turning towards inequality after concluding a campaign to eliminate absolute poverty, pledging to make “solid progress” towards common prosperity by 2035 and “basically achieve” the goal by 2050.

WHAT DOES ‘COMMON PROSPERITY’ MEAN?

“Common prosperity” was first mentioned in the 1950s by Mao Zedong, founding leader of what was then an impoverished country, and repeated in the 1980s by Deng Xiaoping, who modernised an economy devastated by the Cultural Revolution.

Deng said that allowing some people and regions to get rich first would speed up economic growth and help achieve the ultimate goal of common prosperity.

China became an economic powerhouse under a hybrid policy of “socialism with Chinese characteristics”, but it also deepened inequality, especially between urban and rural areas, a divide that threatens social stability.

The push for common prosperity has encompassed policies ranging from curbing tax evasion and limits on the hours that tech sector employees can work to bans on for-profit tutoring in core school subjects and strict limits on the time minors can spend playing video games. read more

This year, Xi has signalled a heightened commitment to delivering common prosperity, emphasising it is not just an economic objective but core to the party’s governing foundation.

Officials say that common prosperity is not egalitarianism.

A senior party official said last month that “common prosperity” does not mean “killing the rich to help the poor”. read more

A pilot programme in Zhejiang province, one of China’s wealthiest, is designed to narrow the income gap there by 2025.

HOW WILL IT BE ACHIEVED?

Chinese leaders have pledged to use taxation and other income redistribution levers to expand the proportion of middle-income citizens, boost incomes of the poor, “rationally adjust excessive incomes”, and ban illegal incomes.

Beijing has explicitly encouraged high-income firms and individuals to contribute more to society via the so-called “third distribution”, which refers to charity and donations.

Several tech industry heavyweights have announced major charitable donations and support for disaster relief efforts. Online gaming giant Tencent Holdings (0700.HK) has said it will spend 100 billion yuan ($15.47 billion) on common prosperity.

Long-discussed reforms such as implementing property and inheritance taxes to tackle the wealth gap could gain new impetus, but policy insiders believe such changes are years off.

A property tax has been discussed for years and two pilots have been implemented in Shanghai and Chongqing since 2011, but little progress has been made.

Other measures would include improving public services and social safety net.

WHAT WILL BE THE ECONOMIC IMPACT?

Chinese leaders are likely to tread cautiously so as not to derail a private sector that has been a vital engine of growth and jobs, analysts said.

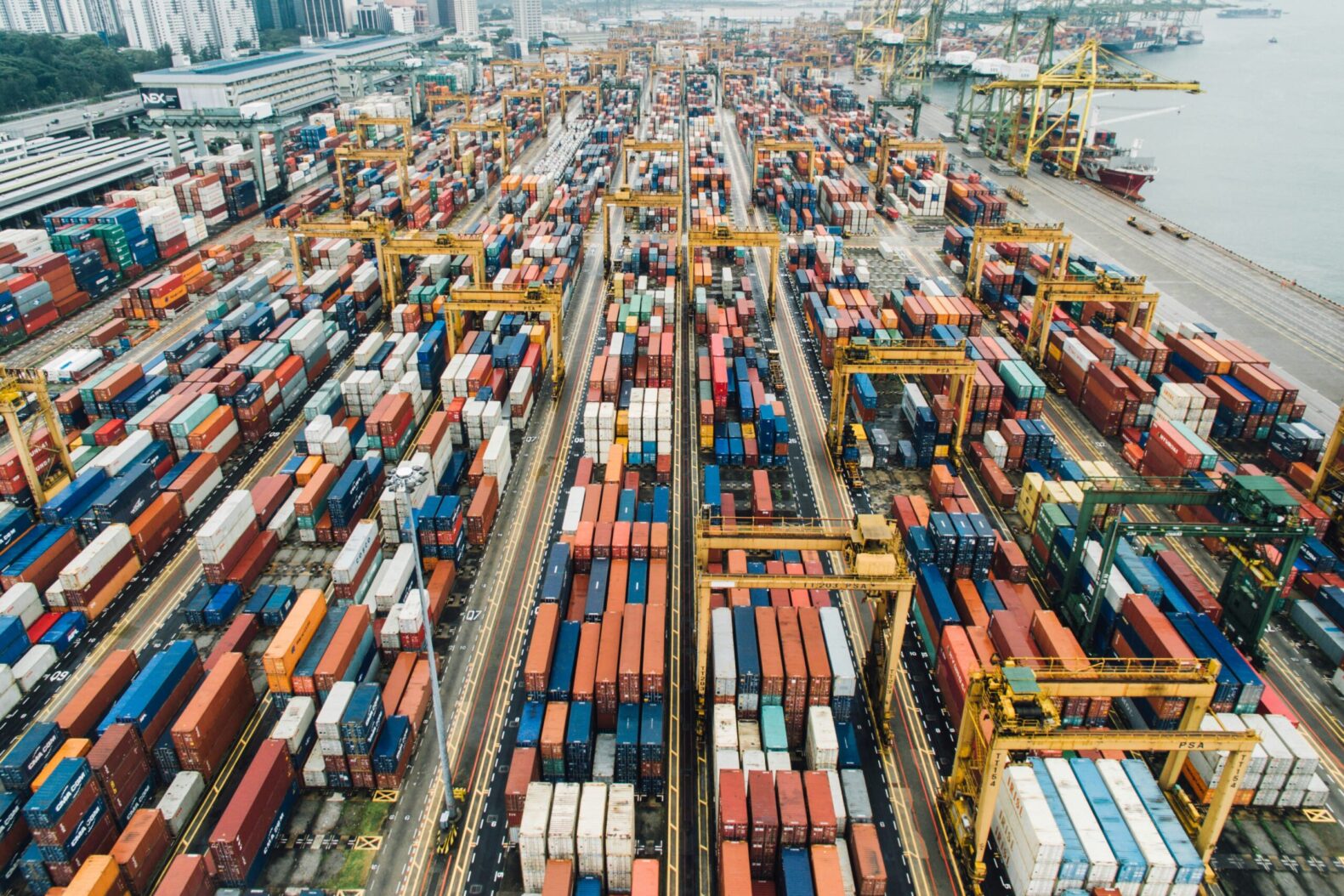

The common prosperity goal may speed China’s economic rebalancing towards consumption driven growth to reduce reliance on exports and investment, but policies could prove damaging to growth driven by the private sector, analysts say.

Increasing incomes and improved public services, especially in rural areas, would be positive for consumption, and a better social safety net would lower precautionary savings.

The effort supports Xi’s “dual circulation” strategy for economic development, under which China aims to spur domestic demand, innovation and self-reliance, propelled by tensions with the United States.

($1 = 6.4622 Chinese yuan renminbi)Reporting by Kevin Yao; Editing by Michael Perry

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles.