Analysis: As EU preps debut recovery bond, a reality check for “safe asset” hopes

As the European Union readies bond sales for its pioneering COVID-19 recovery fund, the scale and duration of the borrowing programme may disappoint those who had visualised last year’s deal for pooled debt as Europe’s Hamiltonian moment.

Agreed in July as the pandemic raged, the deal sparked hopes among investors that Europe would finally have a large and liquid “safe” asset to rival U.S. Treasuries, in turn burnishing the euro’s attraction as a reserve currency.

In short, some predicted, it would do for Europe what Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton did in 1790 for the newly formed United States — create a fiscal union.

Such optimism seemed exaggerated even then. A year on, as the European Commission prepares to sell bonds to finance the 800 billion euro fund, excitement has been tempered by doubts about the fund’s potential to become permanent.

Without that, according to Chris Iggo, chief investment officer for core investments at AXA Investment Managers, the issuance is destined to be “a historical anomaly and the bonds will just get tucked away in insurance company portfolios”.

“This has to be an ongoing thing, there has to be ongoing centralised borrowing capability … otherwise it becomes a one-off thing that’s not very interesting in the long run,” said Iggo, who helps manage 869 billion euros.

“They won’t trade and they won’t be liquid.”

As it stands, recovery fund borrowing will end in 2026. The debt pile will then shrink until the last bonds mature in 2058.

EU budget commissioner Johannes Hahn repeated this week that the bonds were a reaction to a one-off event. The fund was “a strong signal of solidarity” following the pandemic rather than a Hamiltonian moment, he said.

German government bonds are Europe’s fixed-income instrument of reference but at 1.5 trillion euros, the market is a fraction of the $20 trillion outstanding in U.S. Treasuries.

Some had hoped the recovery fund debt would form the basis of an issuance programme to eventually create a risk-free asset which, alongside Bunds, would eventually rival Treasuries.

BLUEPRINT

EU Commission Vice President Valdis Dombrovskis did recently hint that a successful recovery fund offered scope to develop a permanent instrument. Germany’s Green Party, which is likely to join the next government, also wants to make the fund permanent. read more

And the EU has done the groundwork, creating a debt office and a network of primary dealers banks to manage the programme and run debt auctions. Some 90 billion euros in bonds it has sold since October to back its SURE employment scheme already trade more like sovereign securities, enjoying robust liquidity.

But wealthier EU states are likely to oppose any bid to make the fund permanent, and even the current borrowing plan took national parliaments six months to approve.

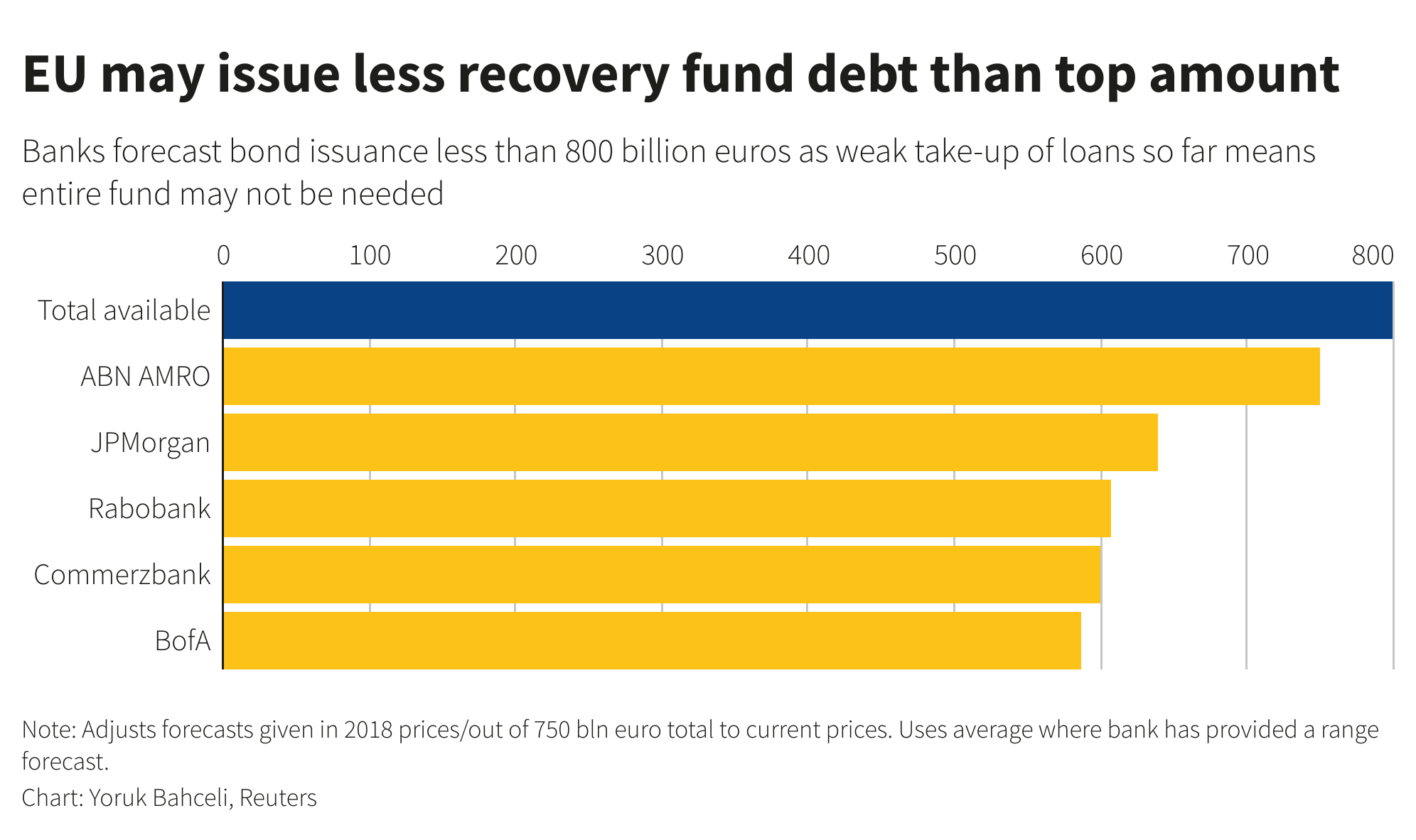

A more immediate risk is lower-than-anticipated issuance volumes, with banks predicting as little as around600 billion euros — 25% below the top amount.

That’s because governments show little interest in taking loans from the fund, which is set up to make grants as well as to lend. Of larger member states, only Italy so far has plans to use the 386 billion euro loan facility, according to Rabobank, although demand is likely to increase with time.

INTEGRATION

And old existential risks remain — without a fiscal union with common budget and tax-raising policies, the EU will remain a supranational, rather than sovereign borrower.

Moreover, the recovery fund lacks a “joint and several guarantee”, meaning that in event of default, each member state will be liable for only a part of, not the entire debt.

Future crises may induce the EU to top up the fund, leading eventually to permanency, said Nicola Mai, a member of the European portfolio committee at PIMCO, one of the world’s largest asset managers.

“If, over time you have a joint and several guarantee and more permanence, you can call it more strictly a sovereign-type issuer,” Mai said.

Until then, investors will demand a premium over Germany’s Bunds to compensate for the slightest risk of a euro break-up, further hampering EU bonds’ safe asset potential.

Currently, the EU pays 24 basis points more for 10-year debt than Germany.

Mike Riddell, who helps run almost 600 billion euros at Allianz Global Investors, sees EU debt becoming the risk-free benchmark “only in an environment where you have complete fiscal integration”.

“Germany is ultimately going to be the risk-free rate for the euro zone for the foreseeable future,” he said.

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles.