Inflation does not faze Britain’s young – perhaps it should

Oct 19 (Reuters) – In online chats to his 132,000 young followers, 19-year-old British social media influencer Joshua Gausden is focusing more on inflation as energy prices surge and the global economy hits bottlenecks.

Most young people do not share the concerns of their parents and grand-parents who remember the runaway inflation of the 1970s and 1980s, even as prices in Britain and around the world are rising sharply.

“I feel like a lot of young people don’t think about this stuff,” Gausden, who is currently studying for a degree in finance, said. “But they are starting to now.”

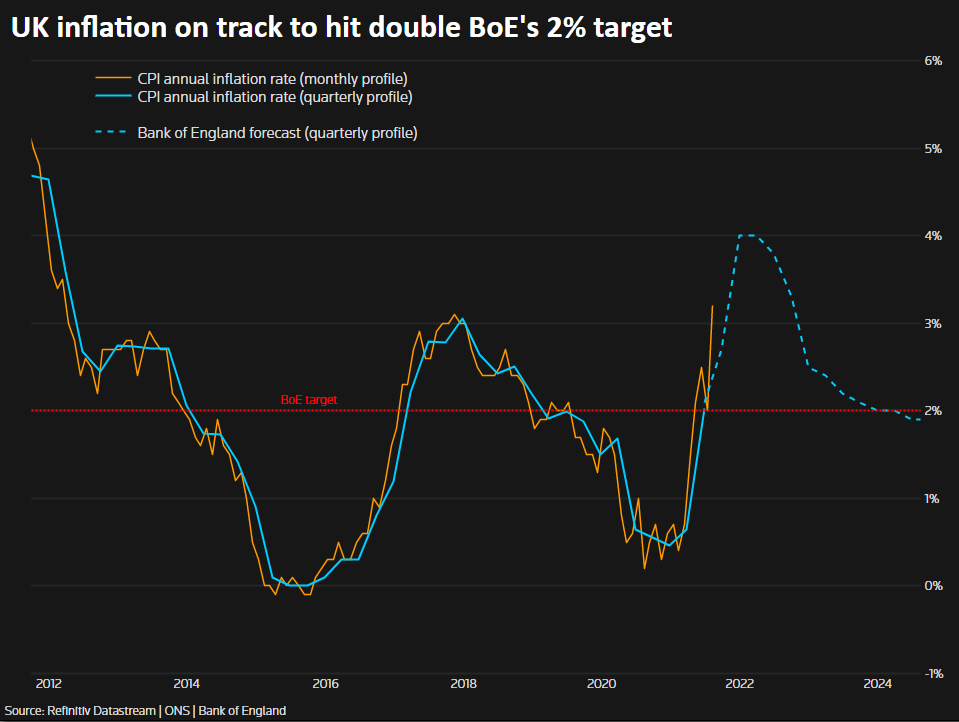

Inflation in Britain has averaged 2% over the past 20 years but now looks set to top 4% at least, more than double the Bank of England’s target. Some economists think it could go as high as 5% or 6% given the recent surge in global energy prices.

While that is nowhere near 1970s levels and is likely to prove less stubborn, Gausden thinks young people should learn from their elders about its corrosive power that threatens to hit them particularly hard. Many are low paid and less able to cope with higher energy bills.

The younger generation also lack the protections that older people have from owning their own homes and their pensions.

“They’re not going to see the effects of inflation until it’s too late,” said Gausden.

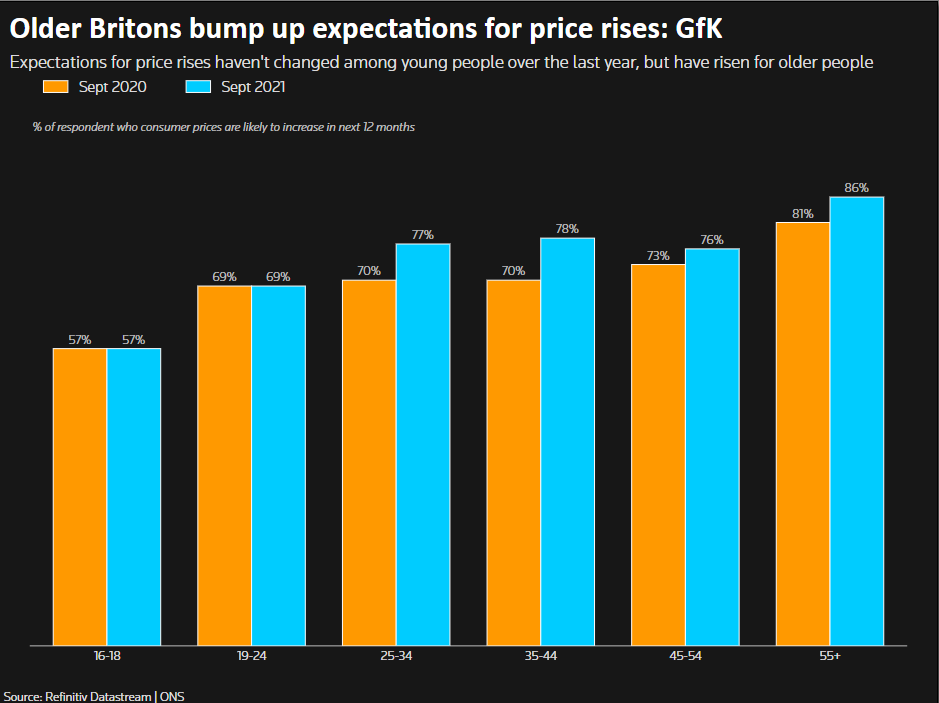

Older people are increasingly predicting higher prices in the 12 months ahead, but expectations among 19-24 year-olds in September remained unchanged from a year earlier, according to data from polling firm GfK.

The worries among older people may reflect how Britain was one of the big world economies hardest hit by the early 1970s oil shock that sent its inflation up to 25% by 1975, a traumatic era for millions of households left wondering whether they would have enough to pay fuel and mortgage bills.

For today’s younger generation, that seems like ancient history.

Andrew McEvoy, 22, an apprentice at an Airbus wing factory near his home close to Liverpool, said only a few of his friends were aware of rising inflation although, by contrast, he is investing now to protect the value of his savings.

“Maybe we’re more unaware, as a generation, of the information around that and what we can do to help ourselves, which is obviously not good because there’s going to be a lot of people who are getting impacted by it,” he said.

TRANSITORY-ISH

Like other central banks, the BoE predicts the rise in inflation will be transitory.

A rise to 5% after the global financial crisis a decade ago faded quickly and policymakers say there is little risk of a 1970s price-wage spiral.

But BoE officials concede that the inflation jump is likely to last longer than they previously thought.

Angus Hanton, an economist who co-founded the Intergenerational Foundation, which campaigns for younger people’s economic interests, said the older generations had an edge when it came to protecting their finances.

“Compared to oldies like me, younger people haven’t had the experience of inflation so they don’t know the tricks of the trade,” Hanton, 61, said.

They included minimising cash balances, taking the likely path of inflation into account when making wage demands and making sure pay deals can be renegotiated regularly.

“Because it happened at a formative time of my life, it’s just instinctive for me,” Hanton said.

As for the government, he said, it should raise taxes on wealth which is largely held by older people, for example via a levy on windfall profits from home sales. That would reduce the burden of taxes paid by working people on their incomes, he said.

But rather than fall, work taxes are set to rise with an increase in social security contributions in April which will help to pay for social care provided typically to older people who have also benefited from generous pension increases.

Another hit for many young people could come from a reported plan by the government to lower the earnings threshold at which student loans must be repaid.

Hanton said the government should carry out an intergenerational assessment of the impact of all policy changes, something already done for the environment.

“Young people have enough to deal with as it is and now we’re throwing in a whole new dimension,” he said.

(This story has been refiled to remove extraneous quote from paragraph 7)Writing by William Schomberg; graphics by Andy Bruce; editing by Mark John and Angus MacSwan

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles.