How sustainable are sovereign wealth funds?

LONDON, Aug 9 (Reuters) – Risks don’t come much longer term than climate change, so you might expect sovereign wealth funds to be all over it, as investment giants with decades in their sights.

Yet the world’s biggest SWFs are making only patchy progress in adapting investment plans to account for environmental, social and governance factors, according to data on energy investments, an ESG analysis of the equity holdings of some of the funds, plus a survey of the players.

Such data provide snapshots into the complex and often opaque world of sovereign funds, which collectively hold nearly $8 trillion in assets.

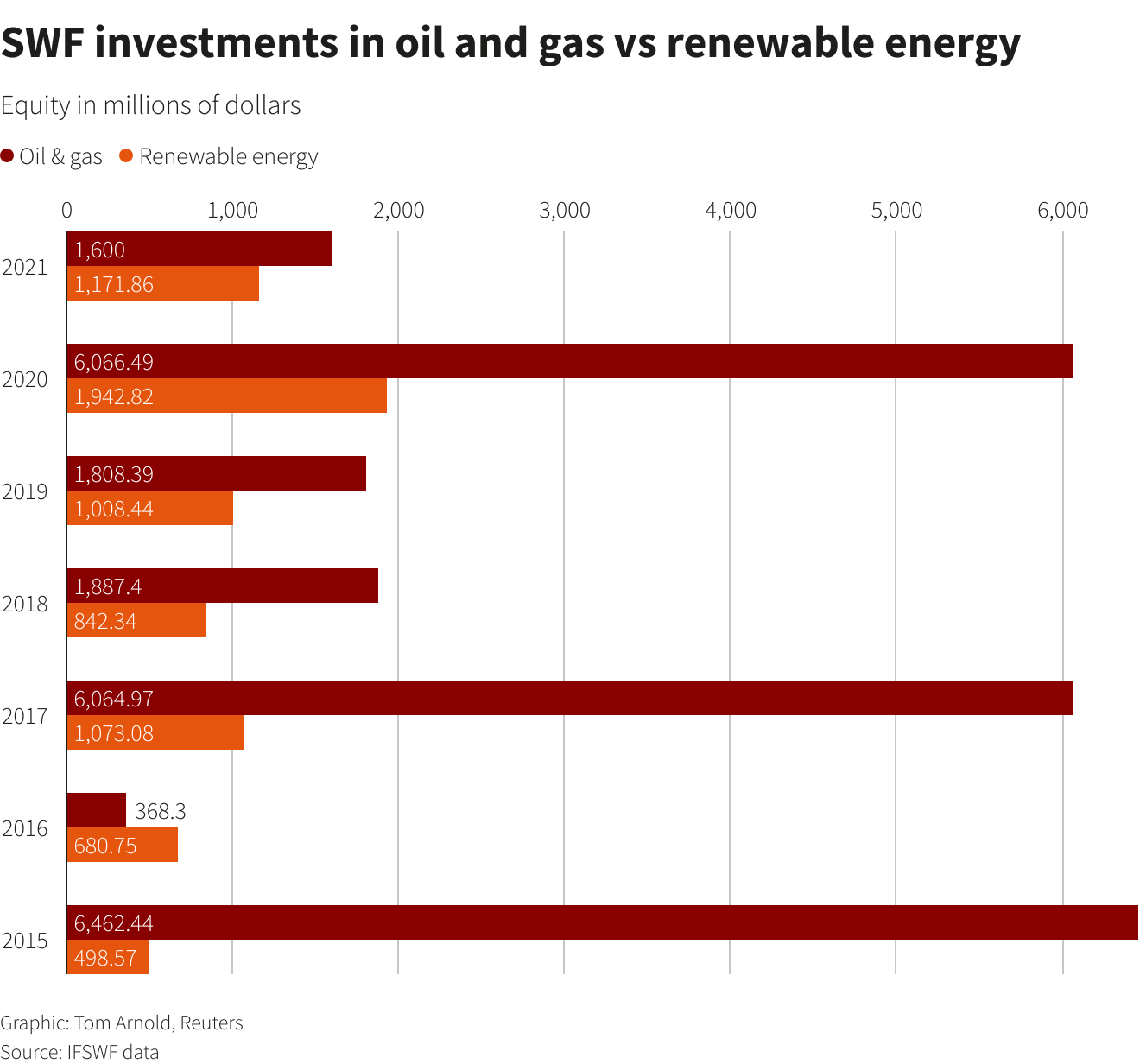

The industry has invested $7.2 billion in renewable energy since 2015, for example, less than a third of the amount poured into oil and gas, data from the International Forum of Sovereign Wealth Funds (IFSWF) showed.

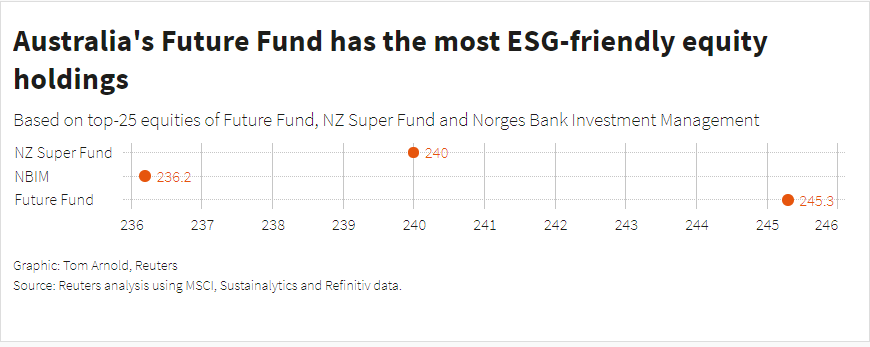

The Antipodean funds, which publicly disclose their investments, scored highly in the ESG analysis of major corporate holdings. New Zealand also said it planned to cut the emissions intensity of its overall portfolio by 40% by 2025, referring to a measure of emissions proportional to revenue.

Middle Eastern funds face a tougher task to decarbonise their portfolios, given their economies’ longstanding reliance on fossil fuels. They did not disclose climate targets, although most are planning to beef up their ESG focus.

The Reuters survey showed a divergence in funds’ broad approaches to companies with poor ESG ratings; Hong Kong Monetary Authority’s fund (HKMA) and Singapore’s GIC prefer to try to drive change from within, while the Antipodean and Norwegian funds are more prepared to twin that approach with excluding stocks.

Any failure or lag in future-proofing portfolios could threaten the long-term performance of SWFs, established to safeguard wealth for generations to come and to buttress state revenues, according to many investment specialists.

And given the funds are some of the world’s biggest investors, their ESG positions can affect how quickly corporations put their businesses on a more sustainable footing, the experts say.

“Sovereign wealth funds are the long-term investment capital of the world, so how they respond to climate change and ESG is the purest case study of how a long-term asset allocator should and does think about these issues, or doesn’t,” said Aniket Shah, Jefferies’ global head of ESG and sustainability research.

“They are the one investor where the term of investment and the term of the scale of these issues are aligned with one another, more than with pension funds.”

OIL AND GAS DEALS

There is broad acknowledgement of the need to change.

Several funds, including those from Abu Dhabi, New Zealand, Norway, Kuwait, Qatar and Saudi Arabia, have signed up to the One Planet Initiative, a drive to integrate climate risks into the management of large pools of capital.

More than 30 funds are also members of the Santiago Principles, a voluntary set of goals aimed at promoting good governance, accountability, transparency and prudence.

Yet progress has been halting for these investment behemoths, who play a role in setting the pace of the global shift away from carbon.

The SWF industry has spent more on oil and gas deals than renewable energy in almost every year since 2015, including 2021 so far, according to the data compiled for Reuters by the IFSWF wealth fund industry group. The one exception was 2016.

In terms of the number of deals over those years, there was a more even split between the two sectors.

Annual investments in renewables are rising, though, while Enrico Soddu, IFSWF’s head of data and analytics, said some oil and gas investments were to help in the transition away from carbon and included pipelines, which could be adapted to carry hydrogen in future.

That said, renewable energy has accounted for less than a quarter of SWFs’ overall number of infrastructure investment deals over the past decade, lagging the 29% of public pension funds, according to Preqin data.

AUSTRALIA SHINES

Comparing funds’ progress on ESG can be difficult, because they vary in history, geography and size. Many invest in areas like infrastructure, real estate and private equity, where progress can be trickier to gauge, while some are more open than others about their holdings.

A snapshot of the top-25 equities of those funds that publicly disclose their holdings – Australia, New Zealand and Norway – showed Australia’s $166 billion Future Fund had the highest-scoring portfolio, according to ESG scores calculated using data from three of the top raters: MSCI, Sustainalytics and Refinitiv.

It was followed by New Zealand’s $41 billion NZ Super Fund and Norway’s $1.3 trillion Norges Bank Investment Management, the world’s largest fund.

“The New Zealand and Australia funds are more ahead than anybody else in terms of integration of climate risk but also ESG in general,” said Massimiliano Castelli, UBS’s head of strategy & advice, global sovereign markets.

SWFs in general have been “a little bit too late” in embracing ESG, he added.

HOW OFTEN DO YOU VOTE?

Wealth funds say climate risk is important, according to the Reuters survey of 13 SWF, though they gave varied responses about their ESG strategies and any targets.

New Zealand is one of the few funds to disclose ESG targets. Norway’s fund said it pushed the companies it invested in to make disclosures about non-financial data, such as greenhouse gas emissions or water consumption.

The $649 billion Abu Dhabi Investment Authority (ADIA) said it incorporated climate risks as part of investment planning, as did Australia’s Future Fund, which said ESG factors “can be material to investment performance”.

Singapore’s $417 billion Temasek Holdings said it assessed the emissions profile of target companies, while the $581 billion HKMA said it was studying metrics and targets to assist its management of climate risk.

How often the funds voted at shareholder meetings – considered by sustainable investment experts to be an element of good ESG governance – also differed.

New Zealand’s SWF said it voted at around 99% of annual general meetings (AGMs) of the companies in its portfolio, while Norway’s voting record was 98%. The Australian fund said it exercised all eligible voting rights in listed companies.

Temasek and the $453 billion GIC didn’t disclose details about how often they voted. HKMA said its external managers exercised voting rights.

Saudi Arabia’s $430 billion Public Investment Fund (PIF), the $534 billion Kuwait Investment Authority (KIA), the $295 billion Qatar Investment Authority (QIA) and the $302 billion Investment Corporation of Dubai (ICD) did not respond to the questions.

The Chinese funds contacted – the $1 trillion China Investment Corporation (CIC) and the $372 billion National Council for Social Security Fund – also did not respond.

RISK-ADJUSTED RETURNS

There are indications that funds that have led the way on ESG have also tended to enjoy better overall financial returns in recent years, according to an analysis by industry research firm Global SWF.

Between 2015 and 2020, New Zealand’s fund had a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 9.5%, Australia’s Future Fund had 8% and Norway’s 7.7%, Global SWF calculated, based on their financial results.

That was ahead of estimates for the likes of the PIF, GIC ADIA, but below those for many public pension funds, which are widely considered more advanced on ESG than wealth funds.

The PIF, ADIA and GIC declined to comment on Global SWF’s estimates.

The precise role of ESG in performance is not clear, though, as other factors are at play, such as investment mandate and asset allocation. Yet Diego López, Global SWF’s managing director, is sure it’s a significant influence.

“There’s definitely a relationship between ESG effort and financial returns,” he said. “Those funds that do not look after proper governance and sustainability do not generally perform very well.”Additional reporting by Gwladys Fouche in Oslo, Anshuman Daga in Singapore, Alun John in Hong Kong, Cheng Leng in Beijing, Saeed Azhar and Davide Barbuscia in Dubai; Editing by Pravin Char

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles.